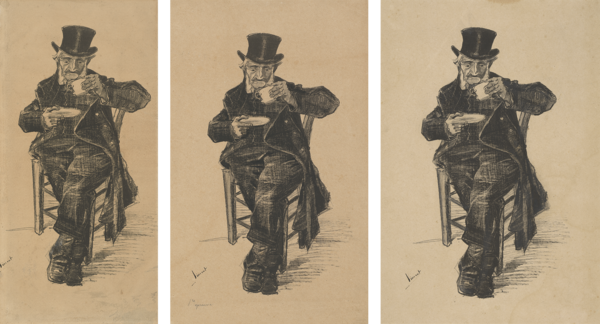

All three prints of Van Gogh’s lithograph Old Man Drinking Coffee have been reunited for the first time since 1882. The location of one of the three was long unknown, but the print was recently rediscovered and subsequently sold at auction. The new owner is now offering the lithograph to the Van Gogh Museum on long-term loan, and will ultimately gift the work to the museum. The presentation opens today at the Van Gogh Museum.

Insight into artistic process

Old Man Drinking Coffee is one of the series of lithographic prints that Van Gogh made in The Hague in autumn 1882. A total of three prints of this lithograph were produced. Two of these prints were already in the Van Gogh Museum collection (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), as was a preparatory study. Van Gogh finished each individual print of Old Man Drinking Coffee by hand. The three lithographs, together with the preparatory drawing, offer a unique insight into Van Gogh’s artistic process. Taken together, the group illuminates changes that the artist made along the way.

The three prints of the lithograph ‘Coffee drinking old man’ – Image at the right is the long-term loan.

Although Van Gogh is best known for his impressive drawings and paintings, tried his hand at the graphic arts for a short while during his time in The Hague (1881-1883). His ambition was to make cheap prints of and for ordinary people, so that everyone could access his work. In doing so, Van Gogh emulated English printmakers whom he admired, who published socially-charged black-and-white illustrations in popular magazines. Incidentally, nothing came of this plan.

Van Gogh made a total of nine different lithographs in various print runs: eight in The Hague, and one in Nuenen (The Potato Eaters). He used transfer paper, a method that he had heard about from his brother Theo in Paris. Van Gogh could draw directly on this specially treated paper, instead of on the lithography stone, which was difficult to handle and required a great deal of experience. A professional lithographer subsequently transferred the image to the stone and made several prints.

Van Gogh’s letters also reveal how he keenly experimented with graphics in The Hague. From November 1882 to April 1883, he frequently writes to his brother and artist friend Anton van Rappard (1858-1892) about the different lithographs that he is making, and about his appreciation for the technique. The provenance of the lithograph now being offered to the museum on loan is notable, as Van Gogh gave it to Van Rappard.

Van Gogh’s most depicted model

The man in the lithograph, with a characteristic face and imposing sideburns, is Adrianus Jacobus Zuyderland (1810-1897), a resident of the Old Men and Women’s Home in The Hague. Zuyderland occupies a special place in Van Gogh’s oeuvre, as the artist portrayed him most often of all of his models. The man can be found in many works, in a number of positions and outfits, and with a wide range of attributes. On this lithograph, the poor pensioner – whom Van Gogh also called ‘the orphan man’ – is wearing the long black coat and top hat that was so typical of the old people’s home where he lived. Van Gogh saw a certain authenticity in figures like Zuyderland, who were marked by a tough life.

The Van Gogh Museum has several copies of each lithograph that Van Gogh made in its collection, but the museum does not have the complete print run of any of his lithographs. The missing final piece of the series Old Man Drinking Coffee was acquired by Monique Hageman, who has worked as a research assistant at the Van Gogh Museum since 1986. Following her death, she will bequeath her lithograph to the Van Gogh Museum. The promised gift means that the Van Gogh Museum will for the first time have a complete print run in its collection. The museum will preserve the group as part of the Dutch national cultural heritage.

I’ve always thought printing a miracle, the kind of miracle by which a grain of wheat becomes an ear. An everyday miracle – all the greater because it’s everyday. One sows a single drawing on the stone or in the etching plate and one reaps a multitude.

Vincent van Gogh, letter to his brother Theo van Gogh, 29 March-1 April 1883, The Hague